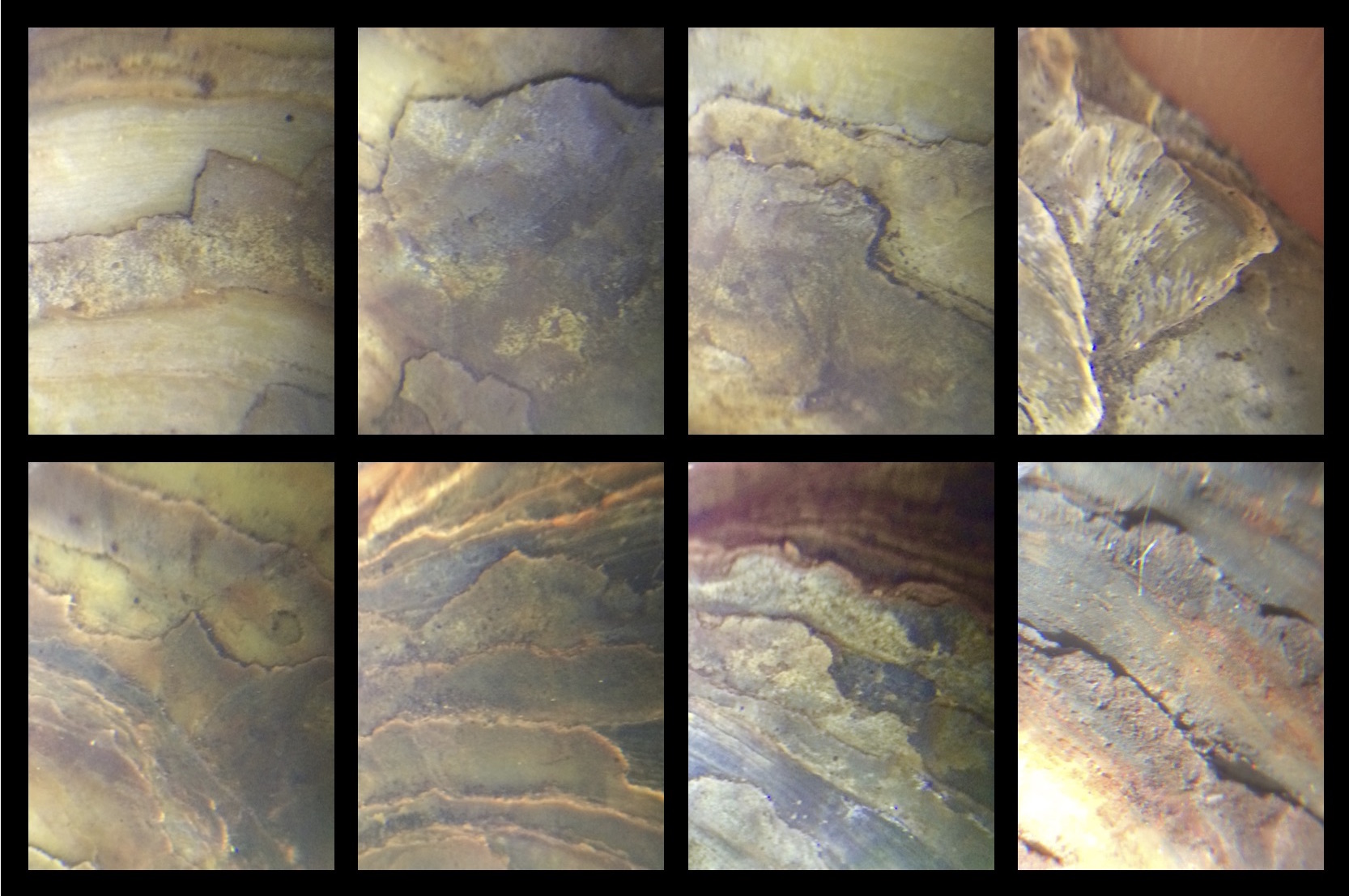

An oyster shell is a rich landscape of material, every one different. Crusty and calcified on the outside, with a smooth, pearly inside made from iridescent layers which form ‘nacre’ or ‘mother of pearl’. The layers, crenulations, waves and sea-bed patterns of the shell speak of the origins of the creature, transporting my imagination to faraway places.

Finding so many oyster shells on site made me re-think it’s status as a ‘midden’, a place where clues to peoples’ lives are to be found through their surviving rubbish. The presence of oysters, speckling the site, so far from their watery home, got me thinking that some of my finds might be older than first assumed. Oysters have been eaten here since Neolithic times and commercially farmed since London was Londinium.

The Roman poet Lucilius says,

‘When I but see the oyster’s shell, I look and recognise the river, marsh or mud, where it was raised.’

It’s possible, with a trained eye, to determine the origin of an oyster from its shell as they are physically affected by the materials of their environment.

This got me thinking about us, the residents of London - how we are we physically affected by the places we grow up in. Is it possible to tell someone’s origin by their clothes, their flesh, or the grain of their character?

Looking closer I try to think myself into the landscape of where the oyster was born and raised, imagining its journey to Bethnal Green, to the person that ate it. I fancy I can see the marks of its shucking, scraping, the angle of the tip to the mouth, almost perceptible.