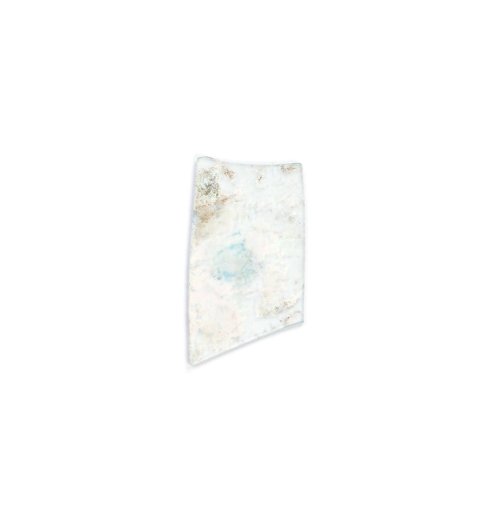

This thin slip of glass was buried deep and dug up again by foxes. It caught my eye, glinting like an opal in the dirt. Its multi-coloured, iridescent surface patina has formed in layers as the glass has been decomposed by water, scoured from the surface and deposited back in fine layers of pure silica, winter upon winter.

Light bounces around within the microstructure of the surfaces, and diffracts, splitting into its constituent parts. When you move and turn the shard, the rainbow patterns thrum and sparkle in blooms of shifting colour, like a cuttlefish’s skin or petrol on the surface of water.

Glass as a material has transformed our view of the world – allowing us to see more, and differently, through windows, mirrors, lenses, scientific instruments and optical fibres, and to understand light itself.

This piece, with its layers of iridescence, has become a material record of its own history – the yearly cycles of weather patterns that formed them laid down like a tree’s rings. I wonder how long it has been buried?

The materials on site at Phytology will transform over millions of years. What will remain, and what will they reveal to whoever might find them?